Sara finally managed to escape the clutches of the Alsaadi-AlKhatib family on the day they were moving apartments. It was 10am, and Ibtissam was busy talking on the phone, and Alaaddein was asleep. She tried the main door, and for once it wasn’t locked. She quickly gathered her papers, her contract and a photocopy of her passport, and left the house. “I walked down the stairs from the fourth floor, and after that I ran.”

She flagged down a taxi, and begged the driver to help her get to the Embassy of the Philippines. She told him she was being abused by her employers. “He told me, come, we will find it for you. He asked every shop where the embassy was. When I saw the flag of the Philippines, I cried because I was so happy. When I tried to pay the driver with the coins I had in my pocket, he refused, and said ‘god will give it to me.’”

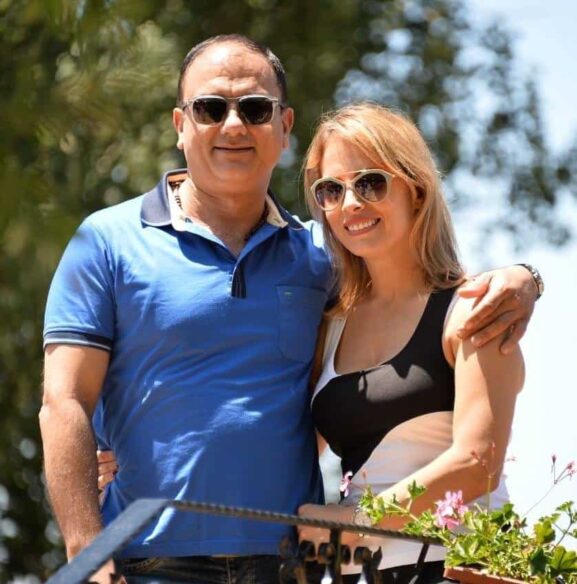

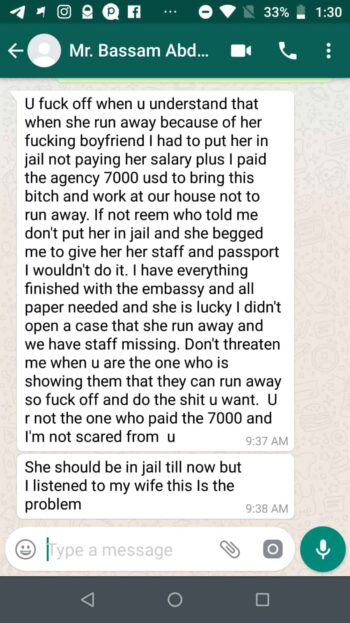

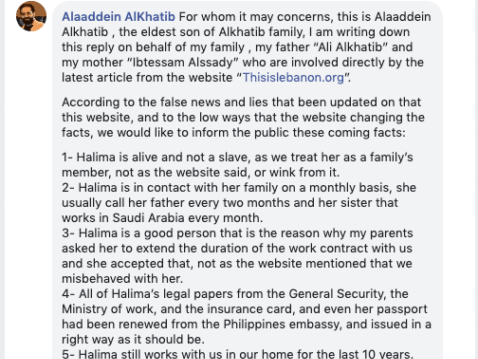

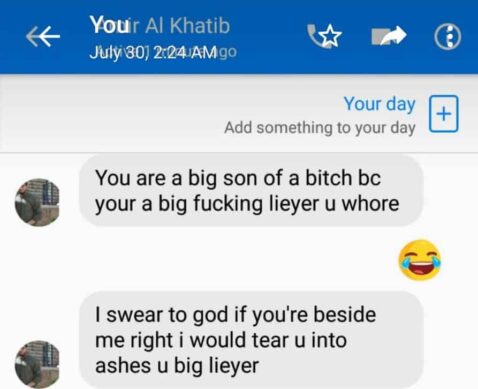

Two days later, Ibtissam came to the embassy to try to get her employee back. She even went so far as to hire a Filipno woman to attempt to lure Sara back, with the promise of $500, a day off every weekend, a salary increase, and a new phone and sim card. Sara refused flat out. The next day, Ibtissam’s husband Ali AlKhatib came to the embassy. “He told me, come back to me, come to our house. I’ll give you food from my hands to your mouth.” When Sara refused to come back with him, he told her: “Hear me, you’re a hemara (donkey) and a fool.”

After her stay at the embassy, Sara was taken to NGO Caritas. Yet again, Ibtissam attempted to get her slave back. This time she came alone. “She wanted to take me. She told me, I can let you work for another family but you need to pay me $5,000.” Sara was advised by the embassy that she had two options: be deported to the Philippines, or find a new employer. She decided on the latter, and worked part time for UN workers. “They treat me well, they are helpful and kind. I work for Swiss, Croatian and Portuguese, Spanish, Irish..”

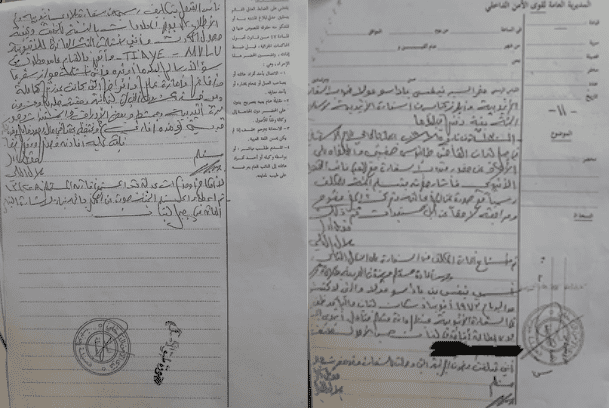

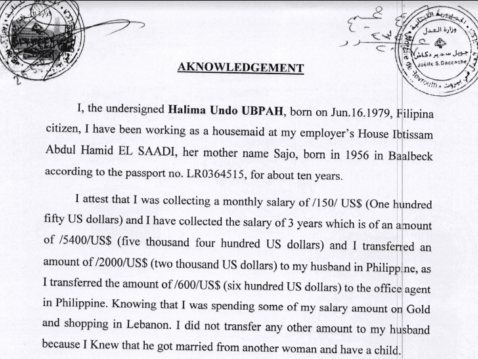

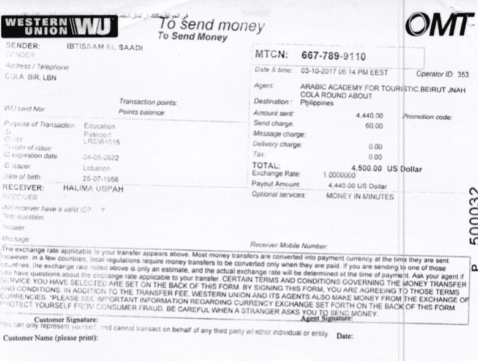

Each time the embassy and Caritas contacted Ibtissam Alsaadi, she insisted that her former employee had to pay her $5,000 before she could release her from the contract. Sara continued to work in Lebanon, and in 2013 she filed a complaint through Caritas, and was allocated a lawyer who contacted Ibtissam Alsaadi on her behalf. But Ibtissam was still asking for $5,000.

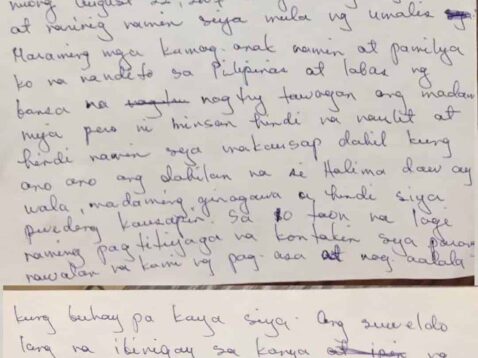

Meanwhile, Sara was following the case of Halima, her successor who was enslaved and abused by Ibtissam Alsaadi and her family for a decade. She questioned why the staff of the Embassy of the Philippines had met the Alsaadi-AlKhatib family in a restaurant in Raouche, and not at the embassy.

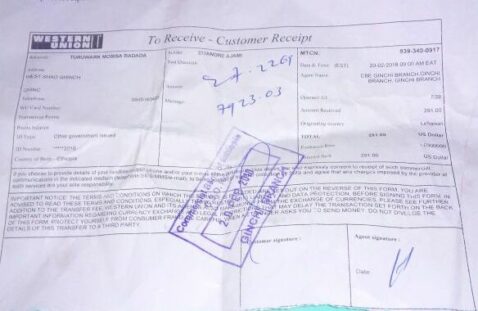

In April 2017, Sara heard that staff changes had taken place at the Embassy of the Philippines, so she decided to try her luck once more. She filed a second complaint, and requested to return home to the Philippines. Sara paid a $2,200 penalty to Ibtissam Alsaadi in return for her papers. At the embassy, she says she encountered many women in similar situations to her own. “There were a lot of other runaways, same as me with different employers but nearly the same experience as me. Maltreatment, lack of food, no salary, even lack of room in the house. They’re asking also for justice.”

She ends her testimony with thanks, and a warning: “I invite you, please don’t go to Lebanon. I know there is still good employers there but I heard a lot of people who are still there and suffering. You are lucky if you survive. You need to be strong. If you still continue [to go to Lebanon], please be brave and don’t let anyone put you down. We are human and we are the ones who can stop human slavery and trafficking.

“I want justice for the Alsaadi-AlKhatib family. I want them to be in jail and be punished by law, and be banned from taking any house maid from any country. I want justice for the damage they did to me and Halima.”